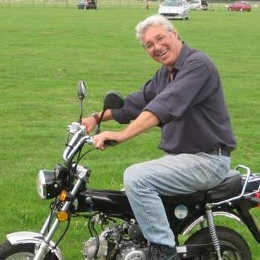

The Stinkwheel Saga

Episode 1

A lifetime’s fascination with minimalist two-wheel transport led David Beare to write The Stinkwheel Saga, Episode 1 v2 together with two fellow members of the British National Autocycle & Cyclemotor Club. This revised second edition contains many colour images and some revised text and tells the story about a mode of transport that became popular in the 1930s. Many readers, including David's classmates from his years at Ecolint will recognize the modern evolution of the stinkwheel as the familiar motorbike, also known as velomoteurs or mopeds.

Mobility for young people normally involved bicycles, trolleybuses, trams, parents with cars or friend’s parents with cars, none of which allowed total freedom of choice as to where or when one traveled. Swiss legislation permitted sub-50cc cyclomoteurs to be ridden from age 14 without need of licences, tests or even helmets, as some might remember those days with fondness, so the freedom bestowed by ownership and use of a cyclomoteur was a complete revelation to this naïve teenager, not to mention that it helped to create an enhanced image with members of the opposite sex and the new-found ability to visit many of them over a wide geographic area. The original thrill of independent travel was never totally forgotten.

“Stinkwheel” was a derogatory term coined in the 1930s to describe small-capacity smelly and smoky two-stroke powered motorcycles; The Stinkwheel Saga is a part-technical, part-sociological, and part-historical book which surveys nine of the most successful clip-on cyclemotor engines, which were fitted to an ordinary pedal-cycle, and sold in Britain from 1945 to 1959. A huge need for affordable personal transport during the post-war period resulted in a plethora of more-or-less successful stinkwheel designs, many designed by aeronautical engineers and made by industrial concerns desperate for work after military contracts had ceased. Most of these motors were unreliable, noisy and oily; the gulf between advertised dream and the daily reality of use was seldom bridged.

This 245-page book is the result of five years research involving many archives, books and magazines, which were plundered for arcane facts, figures, reports and adverts to describe the problems and advantages of cyclemotoring. The Stinkwheel Saga delights the reader with a leavening of dry humour throughout which makes this book different from many others on similar themes. Reading it is enjoyable, even for a non-enthusiast. Illustrated throughout its pages with authentic images from the period, to the extent that modern printing techniques allow, the book provides a genuine flavour of the period and the popularity for this form of personal transport.

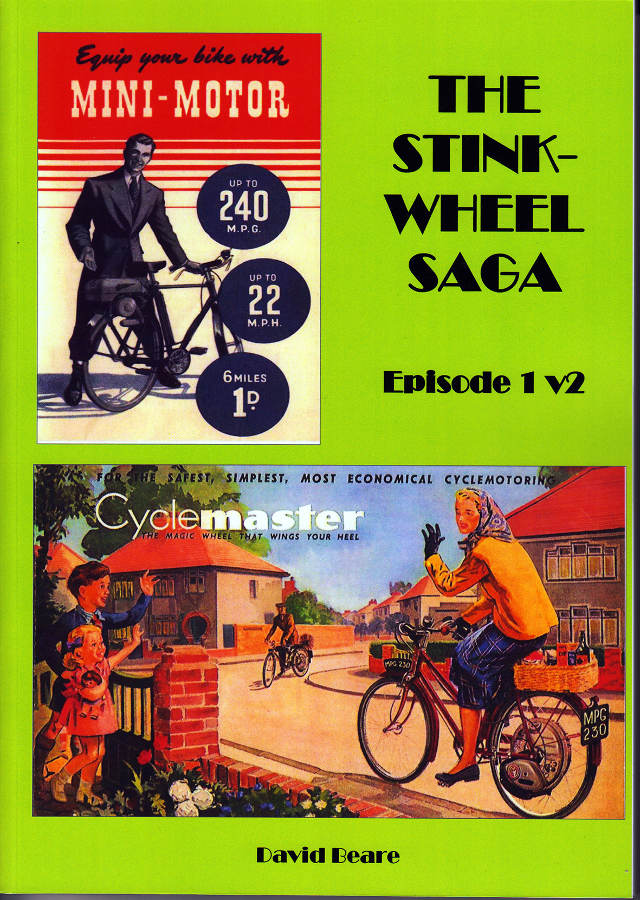

The story of cycle-motoring continues in The Stinkwheel Saga, Episode 2, written with Philippa Wheeler. The second volume extends the scope of this topic by studying many of the commercially unsuccessful makes and makers of clip-on cyclemotor engines. The book is illustrated with more than 300 period photographs and drawings, adverts and extracts from contemporary magazine road-tests.

These cyclemotors were manufactured in many different European countries, including: Holland, Germany, France and Italy. All were facing the same desperate shortage of economical personal transport after the end of WWII. Design parameters of these machines were hence very similar and almost all of the countries reviewed had enacted legislation to allow a maximum engine capacity of 50cc for a cyclemotor which could be ridden without need for taking a motorcycle riding test and obtaining a licence.

A number of unusually-engineered prototypes which never went into production are looked at in detail. The main factor which prevented these prototype motors from becoming accepted were ultimately related to high production costs of these complex “engineers dreams” that rendered them far too expensive for the average bicycle owner who just wanted to put a bit less effort into pedaling and go faster.

Some cyclemotors considered in The Stinkwheel Saga, Episode 2 were home-built specials, made by engineering hobbyists or model engineers who were drawing upon their knowledge of model aeroplane engines, or were simply put together using castings and assembly plans drawn from magazines. One model in particular was designed and built by Ettore Bugatti of Bugatti cars fame, while yet another was based on a piece of agricultural equipment.

Other models failed because prospective manufacturers had procrastinated too long to join the clip-on cyclemotor market trend, which reached it’s peak in the mid-1950s, before declining to oblivion. The demise of the cyclemotor was hastened by the onslaught of cheap European mopeds, which were designed as a single unit and which were far better suited to their task than a bicycle with an attached engine. Increasing prosperity ten years after the end of WWII was also a major factor for the decline in cyclemotors as people could afford better transport and were not prepared to put up with the compromised performance of a cyclemotor.

This book is an entertaining look back at innovations and designs that never came to market, and provides the reader with a better understanding for technology trends that continue to affect our lives.

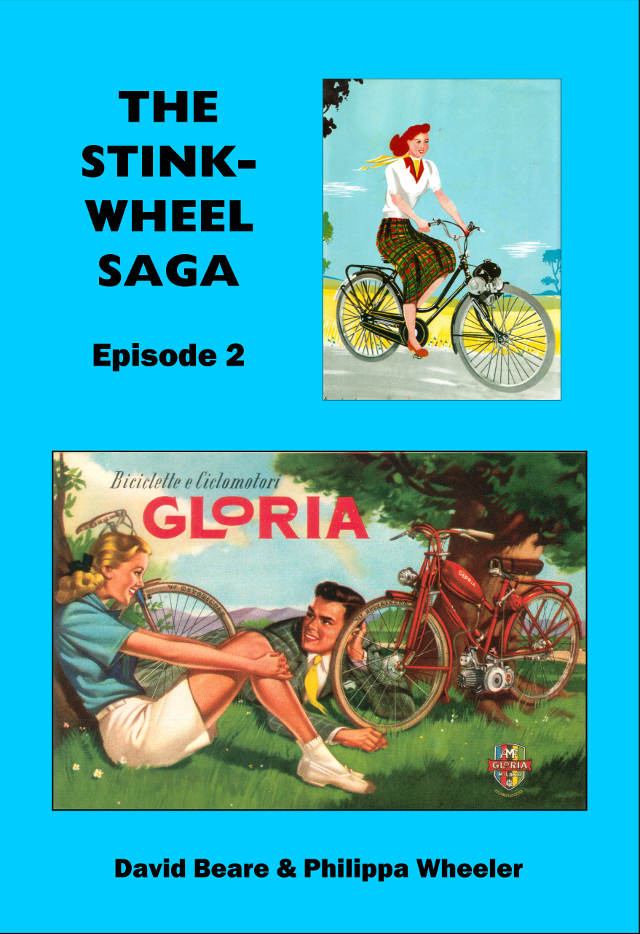

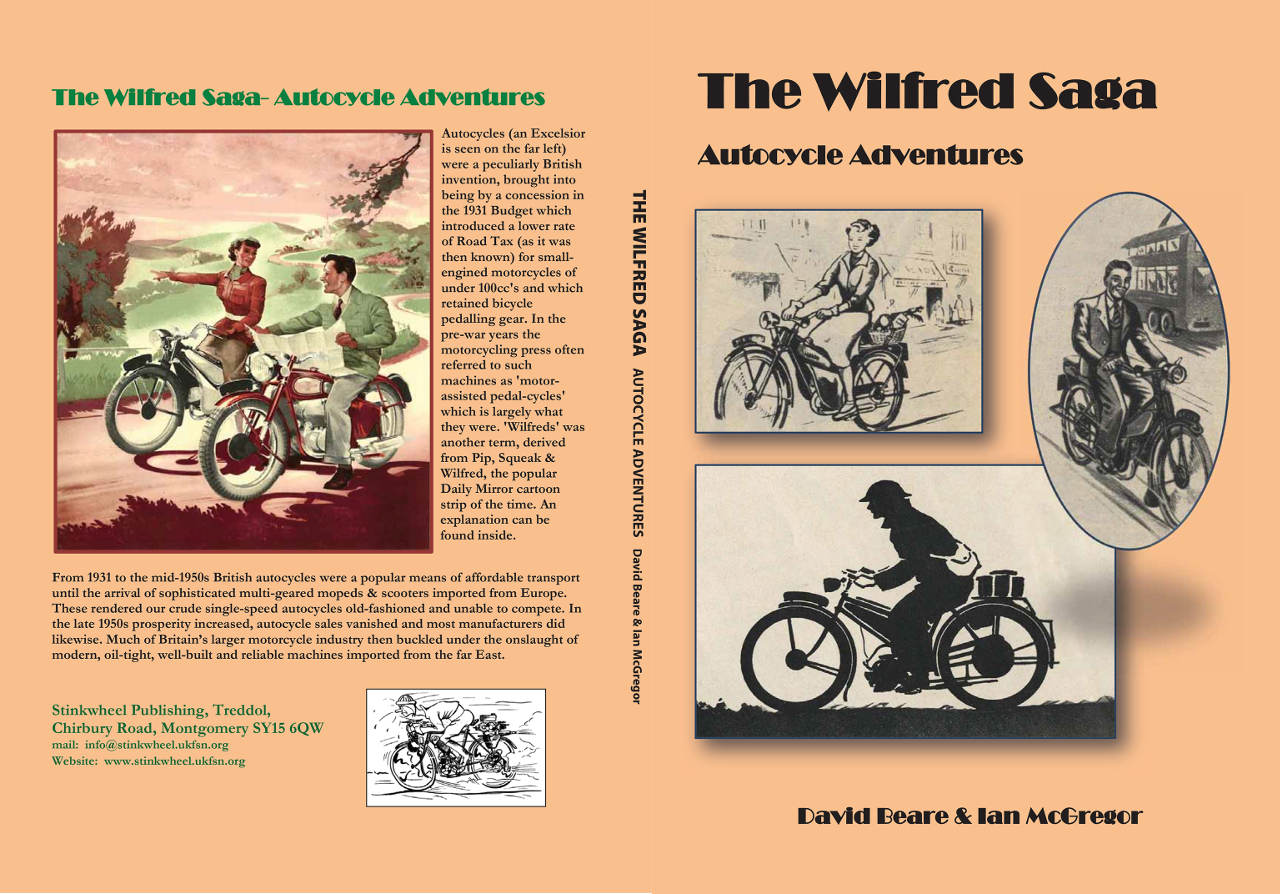

The Wilfred Saga - Autocycle Adventures tells the story of the British ‘autocycle’, a lightweight motorcycle brought into being in 1930 by a concession from the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Phillip Snowden, to allow people to ride the motorized two-wheel cycles without having a motorcycle licence. Engine capacity was limited to under 100cc’s and bicycle-type pedals had to be fitted on the autocycle. Such machines became very popular as a means of cheap, economical, light powered transport, particularly for men or women whose professions, such as midwives or district nurses, required them to travel a lot. Autocycles were a step up from cyclemotors, but not as powerful or heavy as a conventional motorcycle, and had the advantage that running costs were minimised.

The name “Wilfred” comes from a comic strip devised in 1919 for a popular newspaper that featured Pip, Squeak and Wilfred, a dog, a penguin and a small rabbit respectively, an orphaned family of animals who embarked on numerous adventures together. British combatants in WWI were given three medals to commemorate the successful conclusion of the Great War, a combination that some soon renamed as Pip, Squeak and Wilfred. Because Wilfred was very little his name was used to denote small things, and the name was soon applied in a derogatory fashion to small motorcycles and autocycles.

The Wilfred Saga describes in detail the Villiers Engineering engines that were used in the majority of autocycles. Many different British manufacturers, most of which also made conventional motorcycles, produced for the autocycle market from 1934 until it disappeared in the late 1950s, a victim of rising prosperity and a flood of far more modern European mopeds. This book is illustrated with more than 300 colour and black and white photographs that are certain to interest autocycle enthusiasts.

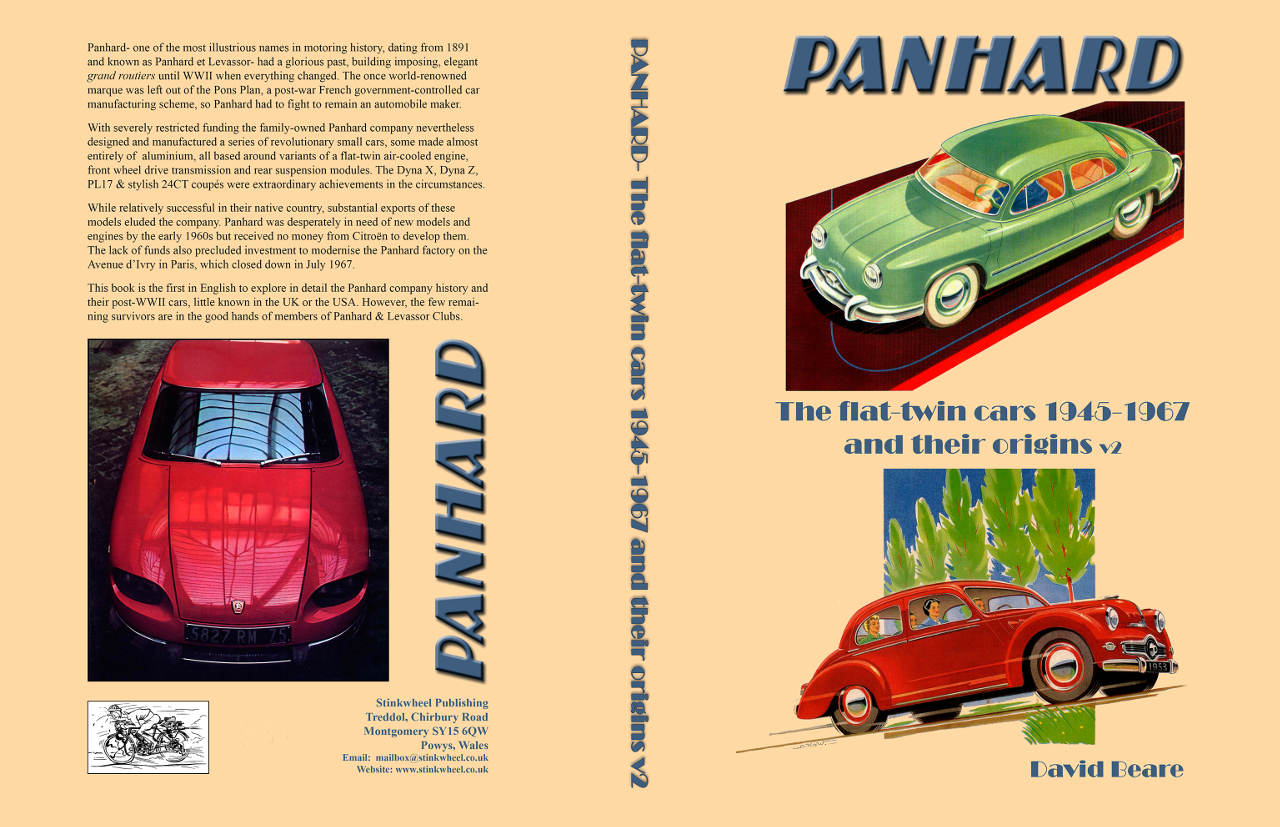

The first comprehensive work on Panhard’s post-WWII economy cars to be written in English, Panhard, the flat-twin cars 1945-1967 and their origins is a history of the Panhard & Levassor company. From its foundation in 1891 as the first company to build and sell automobiles commercially, Panhard enjoyed a period of extraordinary motor-racing successes, and was responsible for the advent of sleeve-valve engines in 1910. Panhard became a successful manufacturer of high-specification luxury cars in the 1920s and 30s, with many models using advanced technologies, but the company was virtually closed down by the Nazi invasion of France in 1940.

During the post-war period, the country as a whole was recovering from a severe economic trough. Reconstruction efforts were initially disorganised, with imposed rationing of all basic commodities and the country endured economic and political upheavals which saw the closure of many previously successful motor manufacturers. Some survived, including Panhard, by designing economical, affordable small cars.

Panhard built ultra-lightweight, all-aluminium cars with air-cooled flat-twin engines based on designs conceived during the dark days of WWII. The revolutionary all-aluminium Panhard Dyna Z1 model was introduced in 1954; it comprised a bare body shell with all closures weighing just 100 kilograms. The car was a six-seater and combined the performance of a larger car with the economy of a smaller car. Its introduction was a huge gamble and almost brought down Panhard, which was forced to seek financial assistance from Citroën in order to survive.

Despite being starved of funding and investment, the old Dyna Z underwent a make-over to become the PL17, and Panhard then surprised everybody in 1963 by launching a very modern 2+2 coupé, called the 24CT. The new coupé might have had a much brighter future had Citroën funded development of a planned four-door long-wheelbase version together with an estate model. Panhard ran out of money and road in 1967, when Citroën closed Panhard’s factory, taking it over to produce Citroën 2CV vans and Ami 6 cars. It became a sad and unnecessary ending for the one-time leader in automobile technology and creator of the world’s first commercially-sold automobiles.

With more than 700 colour and black and white images, this edition is a must read for collectors and admirers of the history of automobiles.

Panhard & Levassor; Pioneers in Automobile Excellence is due for publication in the coming year. It chronicles the Panhard & Levassor company beginning with its foundation in 1891, with the first ever commercial sales of automobiles. The company continued producing through the era of monster racing cars and the ruins of WWI. From 1920 through 1939, Panhard made expensive, glamorous cars for the wealthy as well as trucks and military vehicles, and become known for its advanced technologies during that time.

Following the second war the company struggled to survive. It came up with revolutionary designs for light, economical all-aluminium cars which broke with car engineering traditions. These innovations also broke the bank, forcing Panhard into the arms of another automaker, Citroën, for financial support. When this support was withdrawn and the sales of traditional Panhard models plummeted, the company was then completely taken over and eventually closed in 1967.

This 128 page book comes complete with more than 200 images which illustrate the development of the full range of vehicles produced by Panhard and the innovations that they introduced during the course of the company's 78 year history.

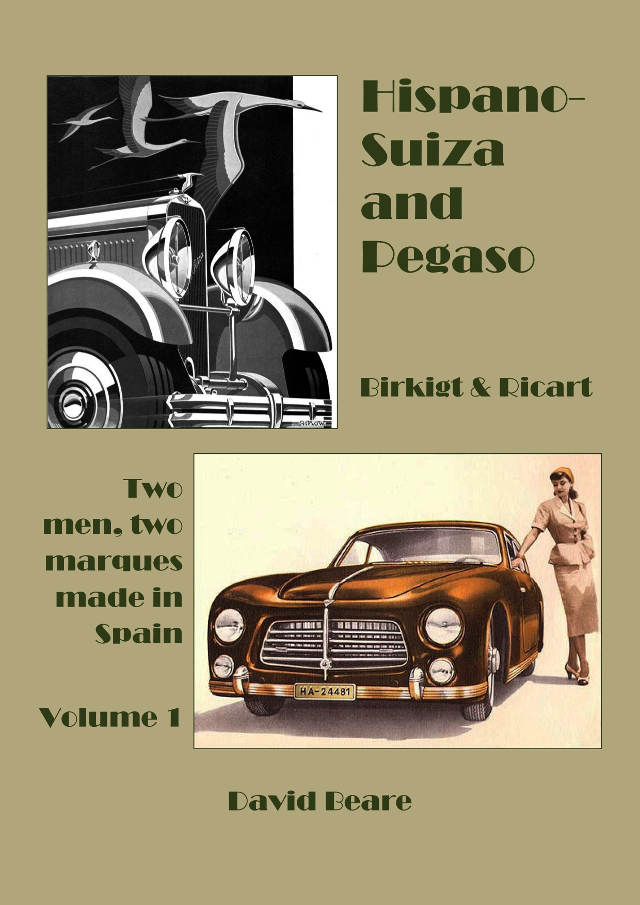

Until the 1960s Spain was rarely considered to be an automobile manufacturing nation; no local automaker had survived for very long as most were largely specialty producers. In 1904 a young Swiss engineer, Marc Birkigt, established a new Spanish automobile manufacturing business in Barcelona called Hispano-Suiza. The company made its fortune during the 1914-18 war by producing aero-engines designed by Birkigt; a French affiliate was also established which became an automobile manufacturer in its own right. This company was justly renowned for some of the most exotic cars of the 1920s-30s, many of which were designed by Birkigt himself. The Spanish company based in Barcelona eventually became overshadowed by the more glamorous French Hispano-Suiza products, but continued to make much-needed vehicles, including trucks and buses, for the Spanish market.

Hispano-Suiza and Pegaso, Birkigt and Ricart, two men, two marques made in Spain is about the Barcelona-based Hispano-Suiza company and uses Spanish sources to tell the story of cars, racing-cars, aero-engines, trucks, buses, military vehicles, guns and aircraft that were made in Cataluña. The first chapter is a brief political, social and economic history of Spain up to and including the 1936-39 Spanish civil war, which shaped the country politically and economically for forty years under the Franco’s dictatorship.

Under the Franco regime, Hispano-Suiza in Barcelona was absorbed in 1945 by a new government department, Empresa Nacional de Autocamiones S.A., and given the job of making desperately-needed trucks, along designs crafted by Wifredo Ricart, a Catalan engineer who had worked pre-WWII for Alfa Romeo in Italy. The truck company was subsequently renamed Pegaso; the history of Pegaso and the vehicles it manufactured are the subject of a second volume. Hispano-Suiza and Pegaso, Birkigt and Ricart is illustrated with more than 300 colour and black and white images that cover the early history of this specialty automotive producer.

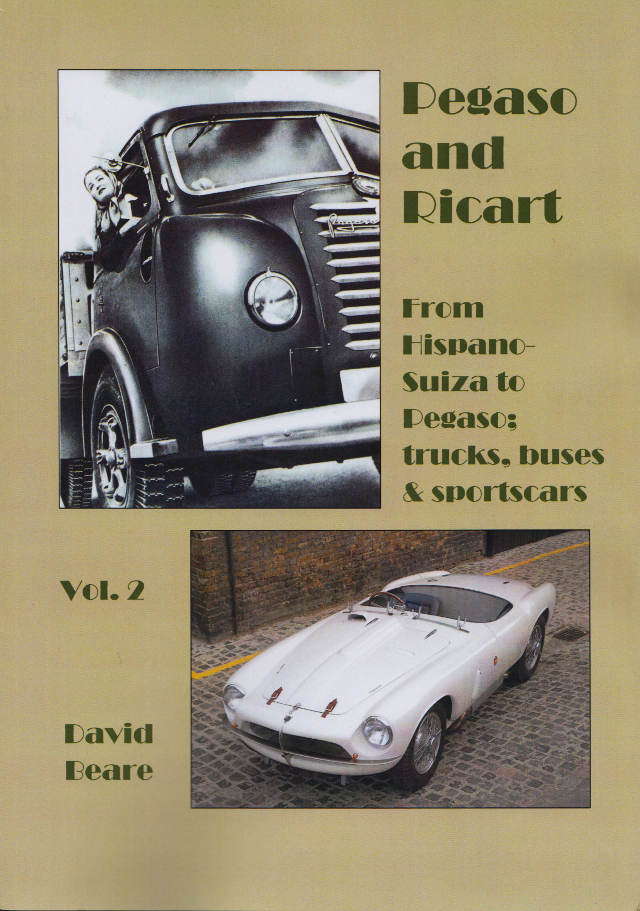

The second volume in this story is soon to be released for publication. Pegaso and Ricart; trucks, buses and sportscars, traces the career of Wifredo Ricart in the 1920s and early 1930s, when he made several attempts at setting up as a car manufacturer but failed. After moving to Alfa Romeo in Milan, Ricart headed a design team responsible for racing cars and aero-engines. He spent the war years in Italy but left in 1945, after being accused by partisans of having collaborated with the Nazis. Ricart returned to Barcelona and was appointed by the Spanish government department INI to establish a national truck manufacturing base called ENASA/Pegaso.

In 1951 Ricart astonished car makers worldwide by introducing a highly-advanced sportscar, the Pegaso Z102, which was to be made by the new Pegaso truck company. With qualified engineers and mechanics in short supply after the destruction caused by the civil war of 1936-1939, the creation of the Pegaso sports-car stemmed from an official program established to train and give hands-on experience of advanced designs and materials to a new generation of Spanish graduates. The resulting Pegaso sports-car design was ambitious and the technology cutting-edge.

Ordering information can be found at stinkwheel.co.uk